In my latest Dragonblade book, Lost in the Lyon’s Garden, I deal with the removal of a loved one of the heroine from a pauper’s grave. What were they? What were the regulations for such burials in the Regency era?

“I COME TO CLAIM MY DEAD.” sketch by artist

First, let us look at the terms often used for such a burial place: Potter’s field. Potter’s field is a term of Biblical origin, a place dedicated for the burial of the bodies of unknown, unclaimed or indigent people. In addition to such dedicated cemeteries, most places have provision for pauper’s funerals to pay for basic respectful treatment of dead people without family or others able to pay, without a special place for interment.

The term “potter’s field” comes from Matthew 27:3–27:8 in the New Testament of the Bible, in which Jewish priests take 30 pieces of silver returned by a remorseful Judas:

Then Judas, who betrayed him, seeing that he was condemned, repenting himself, brought back the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and ancients, saying: “I have sinned in betraying innocent blood.” But they said: “What is that to us? Look thou to it.” And casting down the pieces of silver in the temple, he departed, and went and hanged himself with a halter. But the chief priests, having taken the pieces of silver, said: “It is not lawful to put them into the corbona [A poor box, alms box, offertory box, or mite box is a box that is used to collect coins for charitable purposes.], because it is the price of blood.” And after they had consulted together, they bought with them the potter’s field, to be a burying place for strangers. For this the field was called Haceldama, that is, the field of blood, even to this day. — Douay–Rheims Bible

The site referred to in these verses is traditionally known as Akeldama, in the valley of Hinnom, which was a source of potters’ clay. After the clay was removed, such a site would be left unusable for agriculture, being full of trenches and holes, thus becoming a graveyard for those who could not be buried in an orthodox cemetery.

“Buried in a pauper’s grave” refers to the burial of a deceased person, unable to afford a funeral, in an unmarked or common grave, often called a potter’s field. These graves are for the indigent, unknown, or unclaimed, where bodies are placed when families cannot cover burial costs or identify the deceased. The term can also be used metaphorically to describe someone who is financially reckless and likely to die destitute.

What it means literally

A pauper’s grave is reserved for people who die without the financial means to pay for a traditional burial or who are unclaimed by family.

These burial grounds are also known as potter’s fields, a term with a Biblical origin describing a place where strangers, criminals, and the poor were buried.

Graves in potter’s fields are often unmarked or have simple, low-quality markers, making it difficult to identify the specific individuals buried there.

Why it happens

The primary reason is the deceased’s or their family’s inability to afford a private burial, leading to a public or indigence burial service.

Sometimes, the deceased has no known relatives to claim the body and make burial arrangements.

Historical context

In early history of both England and the eastern U.S., a pauper’s burial was considered a great disgrace and a lasting blow to a family’s reputation.

The coffins used in pauper burials were of poor quality and could crack, sometimes even causing bodies to fall out.

Enjoy this scene from Lost in the Lyon’s Garden where Lord Benjamin Thompson and Lord Aaran Graham attempt to learn whether Miss Victoria Whitchurch’s sister now lies in a pauper’s grave.

Benjamin had known relief when he rode into the circle in the middle of the street upon which he lived. He could see the open door on Miss Whitchurch’s side of the house, and, for the briefest of seconds he thought perhaps she had anticipated his return.

Then he noted the unfamiliar carriage before the house and was immediately alarmed. Benjamin edged the horse closer and dismounted, only to hear a squeal that sounded very much as if it was Miss Whitchurch, as well as cries of alarm.

Without considering the consequences, he charged up the steps. A man stood over Miss Whitchurch, and Benjamin no longer saw reason. She was sprawled at the man’s feet, and he appeared to be prepared to kick her.

Benjamin caught the man from behind, pulling him upward and off the floor to slam the fellow down hard on the brick tiles. Heaving in anger, he lorded over the fellow who was attempting to rise to his knees.

“I advise you to stay down,” he growled, as two women assisted Miss Whitchurch from the floor. “Better yet,” he hissed. “Crawl your way out of my house and never darken my door again.”

“My lord,” Miss Whitchurch rushed to his side, her hand resting on Benjamin’s back, and that flicker of hope had arrived again in his chest. “It is Mr. Betts. He wishes to see the boy.”

“Conceiving a child does not make a man a father,” Benjamin declared in hard tones. “Nor does it make a woman a mother. If you wish to visit the child, find Miss Cassandra and bring her here. Miss Whitchurch would gladly provide her sister access to the child. Otherwise, you should be gone from my home before I count to ten. Never cross over my portal again. One . . . two . . .”

Mr. Betts struggled to his feet as Benjamin continued to count, “Five . . . six . . .” Betts lifted his chin in defiance. “I cannot bring Cassandra here.”

“Eight . . .” Benjamin said over the man’s protests, while Miss Whitchurch demanded, “Why?”

“Because your sister has been dead since early June!”

Benjamin caught Miss Whitchurch when she swooned, scooping her into his arms to carry her to the nearest arm chair, where he sat and cradled her on his lap. Behind him, he knew Patterson and the others escorted Mr. Betts and the women outside. He heard Patterson instruct one of the footmen to accompany the women home safely, while the butler and Brunswick led Mr. Betts to the fellow’s carriage.

Meanwhile, Benjamin held the woman who owned his heart upon his lap. He rocked her as he might have rocked the child. “I have you, love,” he whispered close to her ear.

She moaned and snuggled closer to him. “Cold,” she sighed.

“A blanket, Mr. Patterson,” Benjamin ordered as his butler locked the outside door.

Within less than a minute, Patterson returned with a covering. “Here, my lord.” His man spread a small blanket over Miss Whitchurch’s shoulders and back. “Poor dear,” Patterson murmured.

“See the others, including Mrs. Sullivan and the boy, into the main part of the house and send someone to tend my horse. Miss Whitchurch has had a shock. We will join everyone later.”

“Assuredly, my lord.” Mr. Patterson gently tucked the blanket about the lady before he ushered everyone who was looking on in concern from the room.

“Just rest as long as you need,” he told her. “I will not leave you,” he whispered as he kissed the top of her head. “You are safe with me.”

How long they remained as such, Benjamin did not know nor did he care. The lady required someone she could trust, and, like it or not, he wanted to be that person in her life. Darkness had filled the room before she did more than trace the outline of his stick pin. “Could Mr. Betts have told the truth?” she asked at last.

“I cannot say with confidence,” he replied. “We know your sister did not apply for the cook’s position at The Red Rooster, but we do not know if she found work elsewhere, Now, with Mrs. Taylor’s demise, even if Miss Cassandra searched you out at your former quarters, she would not learn of your directions unless she called at Sustar’s.”

“I thought I heard her that morning in the close when you pulled me into your arms,” she reasoned aloud.

Benjamin did not deny her hopes, though he knew she likely heard what she wanted to hear, as the mind sometimes plays such tricks upon a person. Instead, he said, “With all that has happened of late, I am confident Duncan has not completed his inquiries on your behalf. Lord Liverpool has demanded Duncan’s constant attention, but only a day ago, Lord Graham volunteered to take up the cause. Graham performs often in a covert manner. He has many connections that others do not.”

“Do you think he could discover Cassandra?” she asked softly.

“I will send a message around to him and accept his assistance,” Benjamin assured. “You must understand, if Betts’s words prove true . . .”

“He was likely with her when Cassandra died. Perhaps he had something to do with her death.”

<<<>>>

“Thank you for coming so quickly, Graham,” Benjamin said as he shook his brother’s hand.

“Your message said there was some urgency.”

Benjamin poured them both a drink before he explained his purpose. “I wish to accept your offer to assist Miss Whitchurch in locating her sister.” He motioned Graham to a nearby chair.

“Of course, but what has brought on your heightened concerns?” Graham asked as he lowered his weight into the chair.

Benjamin sat heavily. “God was guiding my steps today. I arrived home to find Mr. Jonas Betts harassing Miss Whitchurch. He had forced himself into the house.”

Graham grinned, his scar puckering his lips on one side. “I pray you kicked his arse into the street. Betts is a prat of the first realm.”

Benjamin sighed heavily. “I was too busy slamming him into the tiled floor to kick his arse. He put his filthy hand on Miss Whitchurch.”

“Next time, remember, we all know permanent ways to be rid of a body.” Graham’s smile widened.

Benjamin permitted Graham’s easy manner to calm his frustration. “Next time,” he said, “I will follow your advice. Yet, what was worse was the dastard said something that I must investigate, but I have no idea where to begin.”

“As I have said previously, I am your servant,” Graham assured. “Do you possess a starting point for our search? What has been done previously?’

“Unfortunately, I have failed the lady in that manner. I have become accustomed to her presence in my house, and I fear I have unconsciously not pursued any leads because I did not wish for Miss Whitchurch to leave. Moreover, it has taken the lady longer than it should have to trust me,” Benjamin admitted. He sighed again. “While I was ordering Mr. Betts from my home, Miss Whitchurch was begging him to bring Miss Cassandra to see the child, to which Betts responded that Cassandra Whitchurch was dead. Has been dead since early June.”

“How would Betts know that?” Graham asked with a frown.

“Betts could have been performing in a purposeful manner to harm Miss Whitchurch, for she repeatedly rejected his advances, even going so far as to take up a position as a teacher in a girls’ school in Bath to avoid him, while the younger sister encouraged Betts’s advances,” Benjamin confided.

“And you came by this information how?” Graham asked with a lift of his brows in apparent amusement.

Benjamin found himself grinning. “I asked what those from Hampshire in Duncan’s office knew of Lord Betts and his son.”

Graham nodded his approval. “Always best to speak to those close to the source.”

Benjamin continued. “Miss Whitchurch has heard nothing from her sister since she left the child in Miss Whitchurch’s room at the boarding house, which is exactly what has Betts’s assertions making more sense—that Miss Cassandra has been dead since early June. As best as we can derive, that was when Titan sent Cassandra Whitchurch to The Red Rooster, though, as I mentioned previously, Duncan and I confirmed the woman never applied for the position as cook at the inn. Since she left the child with her sister, Miss Cassandra has made no attempt to contact Miss Whitchurch. Never even presented her sister one pence for the care of the boy. Though I would not say so to the lady, Betts’s assertion holds more merit than I would like to present it.”

“If Miss Cassandra is dead, without money or identity, she would be likely to be found in a pauper’s grave,” Graham warned. “I can begin there, but I believe it would do me well to speak to Titan and, perhaps, Mrs. Dove-Lyon. To learn more about the young woman. Do you object?”

“Whatever it takes,” Benjamin assured. “We can no longer dance around this craziness. Miss Whitchurch refuses to have the boy christened, though Miss Cassandra told her in the note she left for her sister, to name the child, which sounds to me as if the woman had no desire to face her mistakes every day for the rest of her life. Yet, I cannot say that to Miss Whitchurch. She requires closure before she can claim her own life.”

“Does Miss Cassandra resemble Miss Whitchurch? I will be required to describe her to those I ask.” Graham asked.

Benjamin handed Graham a sketch of Miss Cassandra. It was between two sheets of card stock and tied off with a ribbon. “Miss Whitchurch drew this to show the boy something of his mother as he grew older. She had it put away with the things she brought from the boarding house. I did not ask if she performed so to keep her sister’s memory equally alive for herself, but it may be useful to whoever might have prepared the body for interment, especially if all roads lead to a pauper’s grave as you suggested. For identity purposes.”

“Is it a true likeness?” Graham asked.

“I did not view it, but I have seen several others of Miss Whitchurch’s drawings. She has sketched the child twice, and those were quite good.”

Graham nodded his head in understanding before asking, “I suppose if I find the girl’s grave, you mean to have her exhumed and . . .”

“And buried again on my Kent estate. Her parents cannot accept the girl in their home shire, and I plan to marry Miss Whitchurch, and she and the boy will want to honor Miss Cassandra and remember her. No one in Kent will know more than what I tell them. The child will be an orphan raised by his aunt. I will see to the boy’s schooling and assist him as best I can. Miss Whitchurch and I will present the child the legitimacy his own parents refused.”

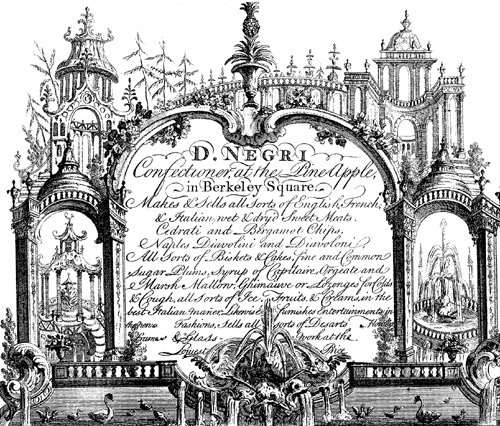

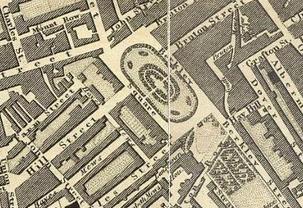

Gunter’s Tea Shop was originally called The Pot and Pineapple.It was located at Nos. 7 -8 Berkley Square. Italian pastry chef, Domenico Negri established it in 1757. The “pineapple” was chosen as part of the name for it symbolized luxury, and pineapples were a common ingredient used in confections. The shop sold English, French, and Italian wet and dry sweetmeats. Custards, cream ice, frozen mousses, jellied fruit, candies, syrups, biscuits, and caramels were served. Some of the cream ice flavors include chocolate, lavender, maple, Parmesan, Gruyere cheese, and bergamot. Mousses were often vanilla, saffron, and pineapple. For more information on sweetmeats, chocolate, and ice cream in Regency England, go

Gunter’s Tea Shop was originally called The Pot and Pineapple.It was located at Nos. 7 -8 Berkley Square. Italian pastry chef, Domenico Negri established it in 1757. The “pineapple” was chosen as part of the name for it symbolized luxury, and pineapples were a common ingredient used in confections. The shop sold English, French, and Italian wet and dry sweetmeats. Custards, cream ice, frozen mousses, jellied fruit, candies, syrups, biscuits, and caramels were served. Some of the cream ice flavors include chocolate, lavender, maple, Parmesan, Gruyere cheese, and bergamot. Mousses were often vanilla, saffron, and pineapple. For more information on sweetmeats, chocolate, and ice cream in Regency England, go

James Gunter became Negri’s business partner in 1777, and by 1799, Gunter was the sole proprietor. During the Regency and throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, Gunter’s was considered a fashionable light eatery in Mayfair, well known for its ices, sorbets, and confections. From the business, Gunter purchased a mansion in Earl’s Court.

James Gunter became Negri’s business partner in 1777, and by 1799, Gunter was the sole proprietor. During the Regency and throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, Gunter’s was considered a fashionable light eatery in Mayfair, well known for its ices, sorbets, and confections. From the business, Gunter purchased a mansion in Earl’s Court. When the east side of Berkeley Square was demolished in 1936–7, Gunter’s moved to Curzon Street. The tea shop closed in 1956, although the catering business continued for another twenty years. Gunter’s was also known for its catering business and beautifully decorated cakes. In 1811, the Duchess of Bedford’s and Mrs. Calvert’s ball suppers featured the shop’s confectionery, a tradition followed by many a society lady.

When the east side of Berkeley Square was demolished in 1936–7, Gunter’s moved to Curzon Street. The tea shop closed in 1956, although the catering business continued for another twenty years. Gunter’s was also known for its catering business and beautifully decorated cakes. In 1811, the Duchess of Bedford’s and Mrs. Calvert’s ball suppers featured the shop’s confectionery, a tradition followed by many a society lady.

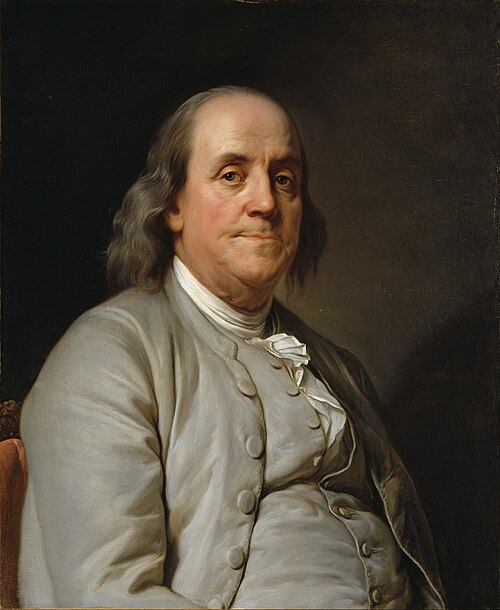

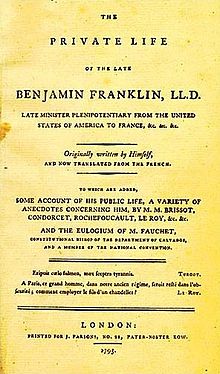

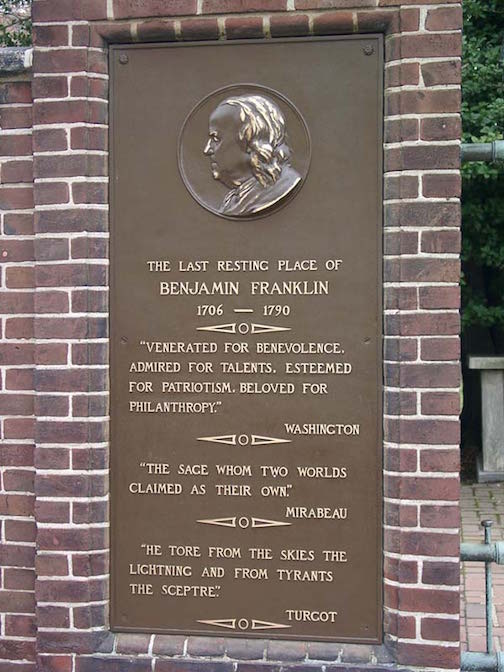

He lived some 30 years in England and Europe. He spent time in London as an ambitious young man. In addition, he lived predominantly in London from 1757 to 1770, where he represented the views of the Pennsylvania colony to the British Parliament. While there he was awarded the honorary degree of “Doctor Franklin.” Artists painted him as a modern-day Prometheus, complete with lightning bolts behind him. The day after his arrival in England, Franklin was summoned to explain the colonial objection to the Stamp Act to the House of Commons. He wrote articles for the British newspapers in hopes of explaining the American point of view, but to no avail. He leaked anti-rebel letters penned by the Massachusetts royal governor. He was arraigned for disloyalty to the Crown in 1774, which resulted in nothing more than his being stripped of his Postmaster position.

He lived some 30 years in England and Europe. He spent time in London as an ambitious young man. In addition, he lived predominantly in London from 1757 to 1770, where he represented the views of the Pennsylvania colony to the British Parliament. While there he was awarded the honorary degree of “Doctor Franklin.” Artists painted him as a modern-day Prometheus, complete with lightning bolts behind him. The day after his arrival in England, Franklin was summoned to explain the colonial objection to the Stamp Act to the House of Commons. He wrote articles for the British newspapers in hopes of explaining the American point of view, but to no avail. He leaked anti-rebel letters penned by the Massachusetts royal governor. He was arraigned for disloyalty to the Crown in 1774, which resulted in nothing more than his being stripped of his Postmaster position. He did fail in convincing the Canadian government in joining the revolt against Great Britain. Returning to Pennsylvania, he was appointed to the Committee of Five, along with Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Roger Sherman and Robert Linvingston, to draft the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson wrote the first draft of the document, but Franklin made one important change. He switched out Jefferson’s “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable” for “We hold these truths to be self-evident.” It was also Franklin who convinced John Morton to break the tie of the Pennsylvania delegation to vote in favor of withdrawing from British rule.

He did fail in convincing the Canadian government in joining the revolt against Great Britain. Returning to Pennsylvania, he was appointed to the Committee of Five, along with Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Roger Sherman and Robert Linvingston, to draft the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson wrote the first draft of the document, but Franklin made one important change. He switched out Jefferson’s “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable” for “We hold these truths to be self-evident.” It was also Franklin who convinced John Morton to break the tie of the Pennsylvania delegation to vote in favor of withdrawing from British rule.

The Disappearance of Georgiana Darcy: A Pride and Prejudice Mystery

The Disappearance of Georgiana Darcy: A Pride and Prejudice Mystery

The Prosecution of Mr. Darcy’s Cousin: A Pride and Prejudice Mystery

The Prosecution of Mr. Darcy’s Cousin: A Pride and Prejudice Mystery